HDB offers a range of lifestyle options for the majority of the population. ADAM TAN explores the new public housing landscape

IF the Resale Price Index (RPI) released by the Housing & Development Board (HDB) is anything to go by, public housing in Singapore is gaining popularity by the day. Quarterly results have recorded just four dips in over five years, with the RPI growing a modest 3.2 per cent annually for the past decade.

|

| Contrast: While the early flats, for example these in Toa Payoh (above), were basic, the latest HDB estates in Punggol (next) will enjoy eco-town facilities as the government plans to remake the estate into a vibrant waterfront town, a recreational and housing hub |

Despite the rising prices, a very visible explanation for this increasing preference for HDB flats would be the evolving lifestyle landscape of public housing estates. Public housing no longer means a collection of cookie-cutter buildings across the island offering exactly the same designs for each flat type.

The fact is that public housing for the masses has come a long way from its beginnings in 1960. The early flats and their surroundings were far simpler than flats and estates built today, with the objective being to house the burgeoning population as quickly as possible.

Fast forward to today and the landscape is very different. New blocks now have lifts on every floor. Individual units and blocks are better designed and estates now incorporate more recreational facilities within them, such as jogging tracks, gardens and exercise areas. Each cluster of flats has its own identity, from the colour of the flat blocks and the design of the playgrounds, to the layout of the greenery in the estate and the amenities offered nearby.

Living in the heartlands has certainly changed over the years, with malls near most estates and an improved infrastructure connecting the residents to the rest of the island via the MRT and Light Rail Transit (LRT) network. Bus services have also improved for greater connectivity.

And it all boils down to an improvement in living standards for the masses. The HDB has progressed from merely providing roofs over people’s heads, to proffering a range of lifestyle options for the mass population.

The Pinnacle@Duxton

A prime example is The Pinnacle@Duxton at Cantonment Road, the landmark public housing development that offers a higher standard of living than previously seen in public housing. Housed in seven 50-storey blocks, The Pinnacle@Duxton also holds the record for being the tallest public housing buildings in Singapore.

Flats for The Pinnacle@Duxton were completed in December 2009 and its new residents enjoy facilities like the two unique skybridges, which create possibly the world’s longest continuous sky garden. These skybridges play a leading role in the lifestyle of residents there.

Flats for The Pinnacle@Duxton were completed in December 2009 and its new residents enjoy facilities like the two unique skybridges, which create possibly the world’s longest continuous sky garden. These skybridges play a leading role in the lifestyle of residents there.

The skybridges, located at the 26th and 50th storeys, offer views of Chinatown, Marina Bay, Mount Faber and the city. Besides that, the skybridge on the 26th floor also incorporates a residents’ committee centre, children’s playground and exercise facilities such as a jogging track, senior citizens’ fitness corner and outdoor gym.

The anticipated demand for the skybridges is such that there are restrictions in place to maintain a level of comfort and safety for all visitors and users. For instance, only 1,000 people are allowed onto the skybridges at any one time and the 26th floor skybridge is reserved exclusively for residents. Furthermore, non-residential access to the sky garden on the 50th floor is chargeable at $5 per person per entry, to help defray maintenance costs.

Rounding off the estate’s amenities are a food centre and daycare centre, while sports and recreational facilities can also be found within the estate. In terms of accessibility, six bus services go to The Pinnacle@Duxton while Outram Park and Tanjong Pagar MRT stations are but a short stroll away.

Rounding off the estate’s amenities are a food centre and daycare centre, while sports and recreational facilities can also be found within the estate. In terms of accessibility, six bus services go to The Pinnacle@Duxton while Outram Park and Tanjong Pagar MRT stations are but a short stroll away.

Two other notable public housing projects are the recent build-to-order (BTO) launches by HDB, namely SkyVille@Dawson and SkyTerrace@Dawson.

Once built, these two BTO projects will be among the closest HDB flats to the Orchard shopping belt. Besides their proximity to Orchard Road, there are also various amenities nearby. These include a supermarket, eateries, parks, schools and recreational facilities.

Mainly because of the location, these public homes are naturally priced on the high side. During the balloting exercise held in September 2008, the price range of 5-room flats at The Pinnacle@Duxton, at $545,000 to $646,000, was comparable only to the median resale prices for 5-room flats in the Central area, Marine Parade and Queenstown (Table 1).

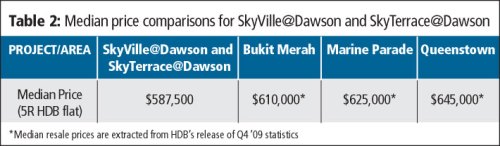

Similarly, the price range for a 5-room flat at SkyVille@Dawson and SkyTerrace@Dawson, at their launch in mid-December 2009, was $532,000 to $643,000. The median price for such units was below the median resale prices for 5-room flats only in Bukit Merah, Queenstown and Marine Parade ( Table 2 below).

For those who may baulk at paying such high prices for public housing, but still crave a vibrant lifestyle in the surrounding environs, Punggol is an increasingly viable, and more cost-efficient, alternative.

In the last 12 months, six out of the 16 BTO projects launched were located in Punggol. The prices of flats there ranged from $228,000 to $322,000 for 4-room flats, and no more than $409,000 for a 5-room flat, roughly 60 per cent of the price tag for the units in SkyVille@Dawson and SkyTerrace@Dawson. In addition, the BTO projects at Punggol also introduced studio, 2-room and 3-room flats to the estate, providing more variety for future residents there.

One factor behind the focus on Punggol is the Punggol21 Master Plan. There are government plans to remake the estate into a vibrant waterfront town, a recreational and housing hub that is also set to be Singapore’s first eco-town for the tropics.

Work on the waterway is set to be completed by the end of the year, and will offer the targeted 21,000 public and private homes along its banks the allure of waterfront living. By end-2011, there will be about 23,000 completed flats in Punggol.

Another exciting development in public housing is Clementi Town Centre. The former bus interchange is set to be unveiled this year as a new 40-storey complex housing a new air-conditioned bus interchange, a five-storey mall, a community library, Town Council office and 388 units of public housing. This will be the first time that a single complex will house public residences, commercial properties and a transportation hub.

In a bid to act as an example of a typical 21st Century HDB town, Punggol is being designed as an eco-town. It will act as a test-bed for various eco-friendly and energy-saving initiatives, such as solar panels to harness energy for lighting common areas, a rainwater collection system and the Energy SAVE Programme. The latter is designed to reduce energy usage in households by 10 per cent over the next five years. These new measures are all part of HDB’s sustainability efforts and Punggol is set to spearhead them.

Then, in January this year, HDB launched the tender for two executive condominium (EC) sites in Sengkang and Yishun. ECs, while considered public housing, offer facilities that are comparable to private condominiums, and have a monthly household income cap of $10,000. These will be the first ECs to be launched since mid-2005, simply because the gap between public housing and mass market private properties had been relatively narrow for years.

However, even as household incomes have been rising, the prices of new launches in the mass market have also been going up.

There is therefore a growing segment of the population whose household income of above $8,000 makes them ineligible for new HDB flats, yet for whom the prices of mass market properties are beyond their means. The demand from this ’sandwich class’ makes the re-introduction of ECs a welcome move from the government.

Staying affordable

In short, all these new developments point to the future of public housing: a richer lifestyle offering enhanced connectivity, more choices for dining, entertainment and education, as well as other amenities, and all within a convenient distance.

And while the government has made it clear that it will not control prices in the property market, it has also stated that public housing will always remain affordable.

Naturally, there will be estates where the prices of public housing units are similar to those of some mass market private properties, but, geographically, prices will never overlap.

To illustrate, one could opt to stay in a centrally located HDB flat or opt for a private property unit in the Outside Central region. That is why Singapore’s public housing will never challenge entry-level private housing.

The choice between one and the other all depends on how status-conscious the buyer is, and whether there is a need for private amenities.

As there is a minimum occupancy period for the new projects, there should be no effect on the resale prices of surrounding flats. The HDB resale price index is expected to see an overall 5-8 per cent growth this year, barring any unforeseen financial crises.

The writer is corporate communications manager, PropNex Realty Pte Ltd

Source : Business Times – 25 Mar 2010